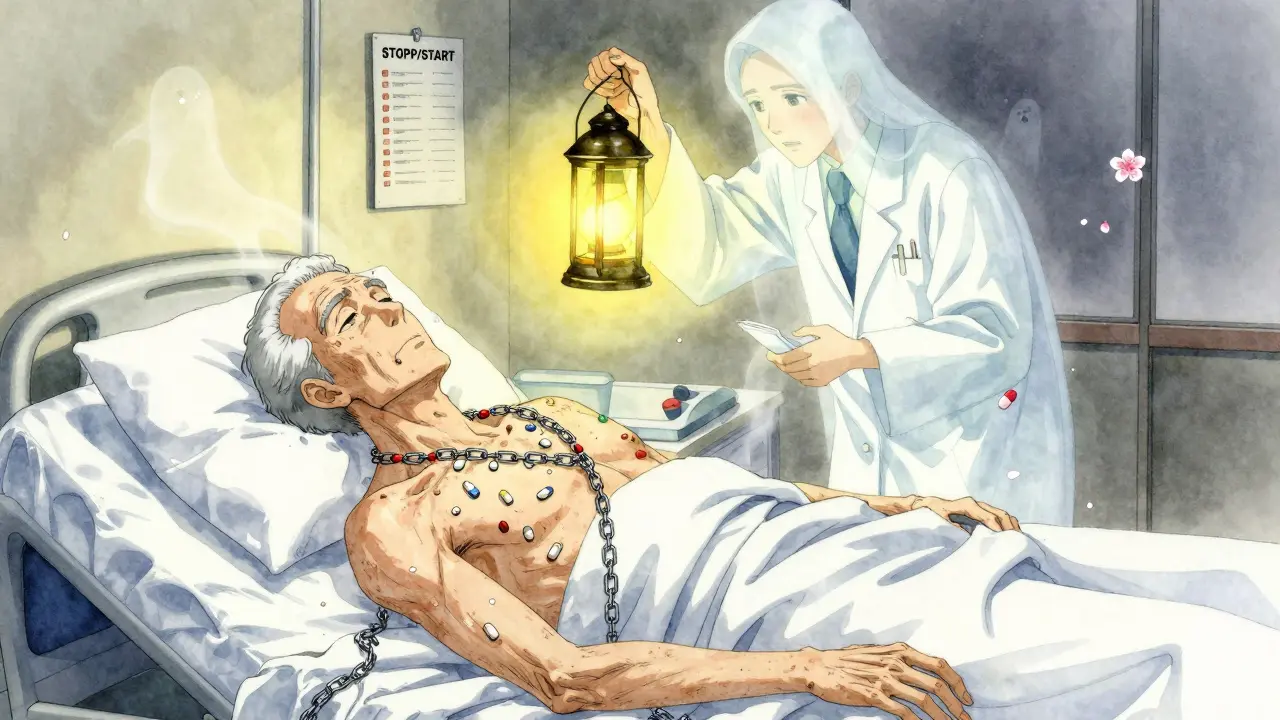

Imagine taking eight different pills every day. Some for blood pressure. Some for arthritis. A pill for sleep, another for acid reflux, and maybe even one for the side effects of another pill. This isn’t a story from a sci-fi novel. It’s the daily reality for polypharmacy in older adults - and it’s becoming more common than ever.

By age 65, nearly half of all Americans are taking five or more prescription medications. For those in nursing homes or with multiple chronic conditions, it’s often 10, 12, even 15. And here’s the scary part: each extra pill doesn’t just add benefit - it adds risk. The chance of a dangerous drug interaction jumps from 6% with two medications to over 50% with five. With seven or more, it’s nearly certain. This isn’t just about confusion or cost. It’s about falls, hospitalizations, memory loss, and even early death.

What Exactly Is Polypharmacy?

Polypharmacy isn’t just taking a lot of meds. It’s taking five or more at the same time - regularly, not just occasionally. The World Health Organization defines it as the use of multiple drugs where the risks outweigh the benefits. But in practice, it’s often not intentional. It’s the result of piecemeal care: one doctor prescribes for heart disease, another for diabetes, a third for anxiety. No one steps back to look at the full picture.

It’s not just prescriptions. Many older adults also take over-the-counter painkillers, herbal supplements like turmeric or ginkgo, and nighttime sleep aids. These aren’t tracked in most medical records. Yet, they can cause deadly interactions. A study of 2 billion patient visits found that 36.8% of older adults were taking 10 or more medications - a number that’s been climbing steadily since 2010. In Europe, it’s 26-40%. In India, nearly half of seniors are on five or more drugs. And in psychiatric care, it’s worse: up to 80% of hospitalized older adults are on multiple psychiatric medications.

Why Does This Happen?

The answer is simple: aging and illness. By age 70, most people have at least two chronic conditions - high blood pressure, arthritis, diabetes, heart failure, COPD, or dementia. Each condition gets its own treatment plan. And each plan adds a new pill.

But there’s more. Doctors often don’t talk to each other. A cardiologist prescribes a beta-blocker. A rheumatologist adds an NSAID for joint pain. The NSAID raises blood pressure - so the cardiologist adds a diuretic. The diuretic causes leg cramps, so a muscle relaxant is prescribed. Then the muscle relaxant causes dizziness, so a sleep aid is added. This is called a prescribing cascade. One side effect gets treated with another drug - not fixed.

Patients rarely question it. They trust their doctors. They’ve been told these pills are necessary. Many believe that if a doctor prescribed it, it must be good. And why wouldn’t they? For decades, medicine has been about adding more - not taking away.

The Hidden Dangers of Too Many Pills

Older bodies don’t process drugs like younger ones. Kidneys slow down. The liver can’t break down toxins as efficiently. The brain becomes more sensitive to sedatives. Even small doses can cause big problems.

Here’s what polypharmacy actually does to older adults:

- Falls and fractures: Sedatives, antipsychotics, and even some blood pressure meds cause dizziness and low blood pressure. One study found that reducing unnecessary medications cut falls by up to 22%.

- Cognitive decline: Medications with anticholinergic effects - common in allergy pills, bladder meds, and some antidepressants - are linked to memory loss and dementia. A single anticholinergic drug can double dementia risk over 10 years.

- Hospitalizations: Half of all drug-related hospital stays in seniors are caused by polypharmacy. Many are preventable.

- Death: Each additional medication after five increases the risk of death. Studies show a direct correlation between pill count and mortality.

- Nonadherence: When someone has 10 pills to take at different times of day, with different food rules, they often forget, skip, or double up. This leads to treatment failure - or overdose.

And the worst part? Many of these drugs are taken long after they’re needed. A statin prescribed 15 years ago. An antidepressant from a divorce 10 years ago. A painkiller for a healed injury. They’re still there - because no one ever asked if they were still helping.

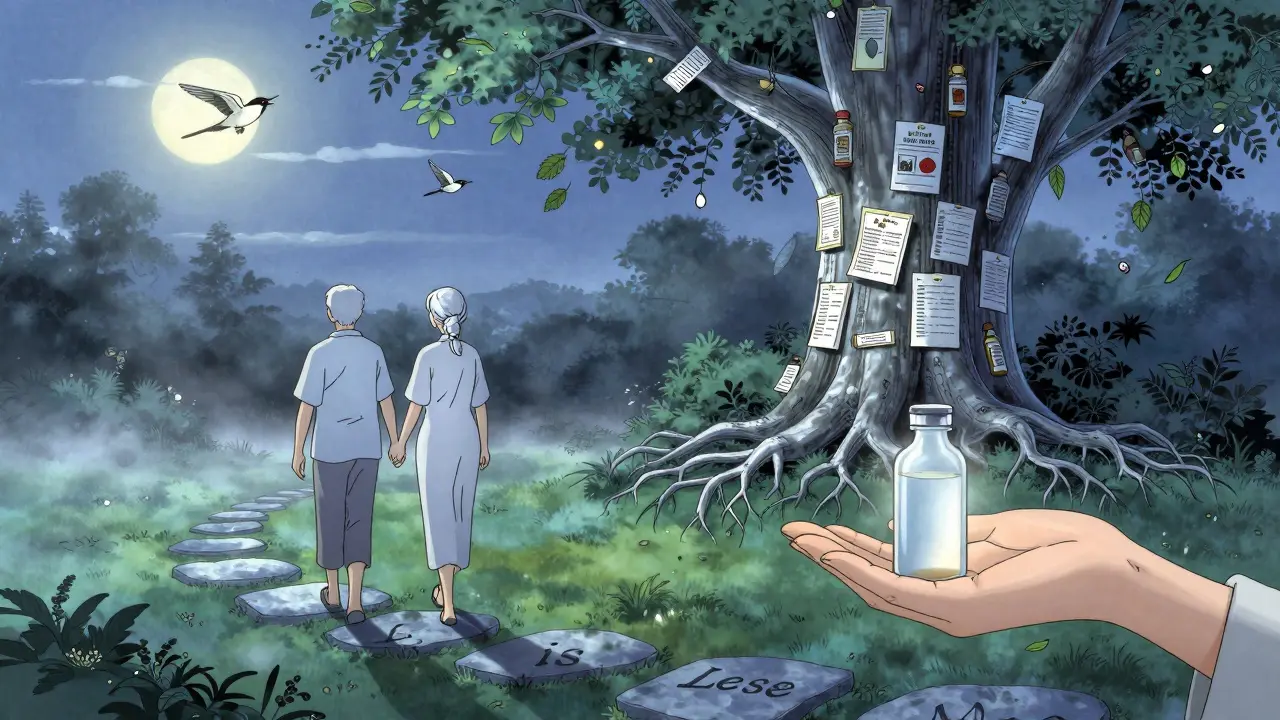

Deprescribing: Taking Pills Away to Save Lives

Deprescribing isn’t about stopping meds cold turkey. It’s a careful, step-by-step process of reviewing every drug, asking: Is this still helping? Or is it hurting more?

The American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria lists medications that older adults should avoid - like benzodiazepines for sleep, certain antipsychotics for dementia, and long-term NSAIDs. The STOPP/START guidelines go further: STOPP identifies harmful drugs to stop; START identifies drugs that should be added but often aren’t - like vaccines or bone-strengthening meds.

Real-world success stories exist. In one nursing home, a pharmacist-led review cut the number of medications per resident from 8.2 to 5.1. Within six months, falls dropped by 30%. Emergency room visits fell by 40%. Patients reported better sleep, clearer thinking, and more energy.

Another study in primary care clinics found that when doctors systematically reviewed medications with patients - explaining why each one was (or wasn’t) needed - 40% of patients stopped at least one drug. Not one patient had a serious withdrawal. Most felt better.

Deprescribing works. But it’s rare.

Why Is Deprescribing So Hard?

Doctors know it’s needed. Patients want to feel better. So why don’t we do it more?

- Time: A full medication review takes 20-30 minutes. Most appointments are 10.

- Training: Few medical schools teach deprescribing. Most doctors learned to prescribe - not to stop.

- Fear: What if the patient’s pain comes back? What if they get anxious again? What if they die? These fears, while understandable, are often based on myths. Most medications can be stopped safely with gradual tapering.

- Patient resistance: Many older adults believe every pill is a lifeline. They worry that stopping one will make them sicker. Sometimes, they’ve been told for years that a drug is "essential."

- System failures: Electronic health records don’t link prescriptions across doctors. Pharmacists aren’t always part of the team. Insurance doesn’t pay for medication reviews.

And then there’s the money. Fee-for-service systems reward doctors for prescribing - not for simplifying. A doctor gets paid for writing a prescription. They don’t get paid for taking one away.

What Can You Do?

If you or a loved one is on five or more medications, here’s what to do - starting today:

- Make a complete list. Write down every pill, patch, liquid, vitamin, and supplement. Include OTC drugs like ibuprofen, melatonin, or antacids. Don’t leave anything out.

- Bring it to one doctor. Choose a primary care provider you trust. Ask them to review it all. Say: "I’m worried I’m taking too many pills. Can we go through them together?"

- Ask the three questions for each drug:

- Why was this prescribed?

- Is it still helping?

- What happens if I stop it?

- Start with one. Don’t try to stop everything at once. Pick one drug that’s least likely to be essential - maybe a sleep aid, an old painkiller, or a vitamin with no proven benefit.

- Go slow. Most drugs can be tapered over weeks or months. Never stop suddenly unless your doctor says so.

- Track changes. Keep a journal: sleep, energy, pain, mood. Note any changes. Share them at your next visit.

Pharmacists are your allies. Ask for a Medication Therapy Management (MTM) session - it’s free under Medicare Part D. They’ll review your entire list, flag interactions, and help you talk to your doctor.

The Future: Better Systems, Better Care

Change is coming - slowly. Some clinics now use AI tools that scan electronic records and flag risky combinations. Pharmacist-led teams are embedded in geriatric clinics. Medicare is starting to pay for comprehensive medication reviews. The CDC is pushing for deprescribing guidelines for common drugs like benzodiazepines and proton pump inhibitors.

But the real breakthrough won’t come from technology. It’ll come from changing how we think. Medicine doesn’t have to mean more pills. Sometimes, less is more. Sometimes, the most powerful treatment is not adding something - but removing it.

For older adults, fewer medications often mean more life - clearer thinking, fewer falls, better sleep, and more time with family. The goal isn’t to take fewer pills for the sake of it. It’s to take only what truly helps - and let go of what doesn’t.

Is polypharmacy always dangerous?

Not always. Some older adults need five or more medications to manage serious conditions like heart failure, diabetes, or kidney disease. The problem isn’t the number - it’s whether each drug is still necessary, effective, and safe. A pill that helped at 65 might be doing more harm than good at 80. The key is regular review - not automatic continuation.

Can stopping medications make me sicker?

Sometimes, but rarely. Most medications can be stopped safely with a gradual taper. For example, stopping a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) for acid reflux might cause temporary heartburn - but that usually fades in weeks. The bigger risk is continuing drugs that cause dizziness, confusion, or kidney damage. Studies show that carefully planned deprescribing improves quality of life without increasing health risks.

What are the most dangerous drugs for older adults?

According to the Beers Criteria, the most risky include: benzodiazepines (like lorazepam) for sleep, antipsychotics (like risperidone) for dementia, NSAIDs (like ibuprofen) for long-term pain, and anticholinergics (like diphenhydramine in Benadryl or oxybutynin for bladder control). These are linked to falls, memory loss, kidney damage, and increased death risk. Many are still prescribed routinely - even though safer alternatives exist.

Who should lead a medication review?

A primary care doctor should start the conversation, but a pharmacist is often the best person to do a full review. Pharmacists are trained to spot interactions, duplicate prescriptions, and outdated meds. Medicare Part D covers free Medication Therapy Management (MTM) sessions for eligible patients. Ask your pharmacy or doctor if you qualify.

How often should I review my medications?

At least once a year - but ideally every time you see a new specialist or after a hospital stay. Medication needs change as health changes. A drug that helped after surgery might not be needed six months later. If you’ve been on the same list of pills for five years without a review, it’s time to ask for one.

If you’re caring for an older adult, don’t wait for a crisis. Start the conversation today. Ask for the list. Ask why each pill is there. Ask what happens if it’s stopped. You might just help them live better - and longer.

Jayanta Boruah

February 22, 2026 AT 00:39It is a well-documented phenomenon that polypharmacy in geriatric populations constitutes a systemic failure of care coordination rather than a clinical necessity. The data from the WHO and CDC are unequivocal: each additional medication after the fifth introduces an exponential increase in adverse events. In India, where polypharmacy prevalence exceeds 45% among seniors, the absence of centralized pharmacovigilance systems exacerbates the issue. Over-the-counter NSAIDs, Ayurvedic tonics, and unregulated herbal supplements are frequently co-administered without documentation, leading to pharmacokinetic clashes that primary care physicians are ill-equipped to detect. The prescribing cascade is not an anomaly-it is the default mode of practice in fragmented healthcare environments. Deprescribing is not merely advisable; it is an ethical imperative.

Hariom Sharma

February 23, 2026 AT 15:21bro this hit home. my dad was on 12 pills a day-sleep aid, blood pressure, arthritis, acid reflux, vitamin D, turmeric, fish oil, and a pill for the side effects of another pill. one day we just started cutting one at a time. he said he felt like a new man. no more dizzy spells, slept better, actually remembered our birthdays. turns out half those meds were from 2010. no one ever asked if they still worked. just kept adding. we need to stop treating pills like trophies.

Nina Catherine

February 24, 2026 AT 07:16omg yes!! i’ve been trying to get my mom to review her meds for years but she’s terrified to stop anything. i printed out the beers criteria and we went through it together-she had benadryl for allergies AND for sleep?? and a muscle relaxant from a sprained ankle 8 years ago?? we stopped the benadryl first and her brain fog cleared in 3 days. i’m so glad this article exists. also, pharmacists are LEGENDS. ask for mtm!! it’s free!!

Taylor Mead

February 24, 2026 AT 20:40really solid breakdown. i work in geriatrics and the biggest barrier isn’t the meds-it’s the mindset. patients think stopping a pill = giving up. we need to reframe deprescribing as ‘reclaiming’-reclaiming energy, clarity, mobility. one 84yo told me, ‘i didn’t realize i was tired because i’d been tired for 15 years.’ once we tapered his anticholinergic, he started gardening again. that’s the win.

Amrit N

February 25, 2026 AT 12:36so true. my grandpa took 11 pills daily. we cut 4 of them over 3 months. he didn’t even notice at first. then he said, ‘i think i can walk to the mailbox without stopping.’ simple stuff. but life-changing. pharmacists are the real heroes here. if you’re in india, ask for a med review at any big pharmacy-they’ll do it for free if you ask nicely.

Robert Shiu

February 25, 2026 AT 18:51just had a patient last week who was on 14 meds. she cried when we told her she could stop half of them. said she felt guilty for not taking ‘everything’ her doctors gave her. we started with the sleeping pill and the old antidepressant. within 10 days, she was sleeping better and said she felt ‘lighter.’ not because we took something away-but because we gave her back her own body. this isn’t about fewer pills. it’s about more life.

Scott Dunne

February 26, 2026 AT 09:11It is beyond lamentable that American healthcare has descended into a pharmaceutical carnival. The notion that more drugs equate to better outcomes is not merely misguided-it is criminally negligent. The Irish model, where comprehensive medication reviews are embedded in primary care, demonstrates that systemic change is possible. Why do we tolerate this? Because profit drives policy. The pharmaceutical lobby funds 90% of continuing medical education. The solution is not education-it is structural reform.

Ashley Paashuis

February 27, 2026 AT 16:19As a geriatric nurse practitioner, I can confirm: deprescribing is the most underutilized intervention in our field. The Beers Criteria is not a suggestion-it’s a mandate. We routinely see patients with chronic kidney disease on NSAIDs, or dementia patients on antipsychotics for agitation that stems from unaddressed pain or infection. These aren’t treatment failures-they’re diagnostic failures. A thorough review, done with empathy and evidence, transforms lives. And yes-it’s safe. The data is overwhelming.

Marie Crick

February 28, 2026 AT 10:07I’ve seen too many elderly people turned into walking pill cabinets. It’s not healthcare-it’s pharmaceutical exploitation. Someone needs to hold these doctors accountable. These drugs aren’t just unnecessary-they’re poisoning our parents. Stop prescribing like it’s a contest. We’re not fixing aging. We’re drugging it into silence.

Liam Crean

February 28, 2026 AT 17:14My mom’s story: 8 pills. We stopped the statin (she had no heart disease history), the sleep aid, and the acid reflux med. She didn’t get worse. She got better. More alert. Less constipated. Less confused. I think we’re scared to admit that sometimes, the best medicine is doing nothing. The system doesn’t reward that. But families can. Start with one pill. Ask why. You might be surprised.